LUJ Students Visit Showa Kinen Park in Tokyo

On November 24, Dr. Adam Tompkins, LUJ Professor of History, took his Environmental History of Japan class to Showa Kinen Koen, the largest park in Tokyo.

Since at least the 1920's, in the wake of the Great Kanto Earthquake, the Tokyo government had desired a way to make their city greener, but that proved very difficult with the coming of war and then rapid postwar urbanization. After World War II, the American military took control of Tachikawa Air Base from the imperial army and sought to extend the runway northwards to accommodate jet aircraft. When the plans for enlargement were made public in 1955, according to Dr. Tompkins, "a massive grassroots anti-base expansion movement took form," known in English as the Sunagawa Struggle, or Sunagawa Toso. Many local residents refused to sell their land and organized sit-ins and protests to interfere were land surveying efforts. Japanese students, many of whom belonged to the student-run national organization Zengakuren joined the opposition, adding important numerical strength to the growing anti-base movement. The protests drew greater public sympathy as police used excessive force against peaceful demonstrators.

Ultimately, the continued opposition strongly influenced the decision to not only halt the expansion but close the base. Eventually, in 1977, the American military gave the land back to Japan, two years after the formal end of the Vietnam War. Tachikawa Air Base was shut down and operations moved to Yokota. Showa Kinen Park, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, was constructed on a portion of the western half of the air base.

The Sunagawa Struggle, however, has been, in a way, swept under the rug of 20th century Japanese history. "What makes Showa Kinen Park particularly interesting," explains Dr. Tompkins, "is that it effectively erases the military-industrial history of the area and erases the history of one of the most significant (because it was successful) anti-base movements in modern Japanese history."

The park is around a quarter of the size (180 hectares) of New York's Central Park—a massive urban green space, especially when you think of the size of regular Japanese parks in general.

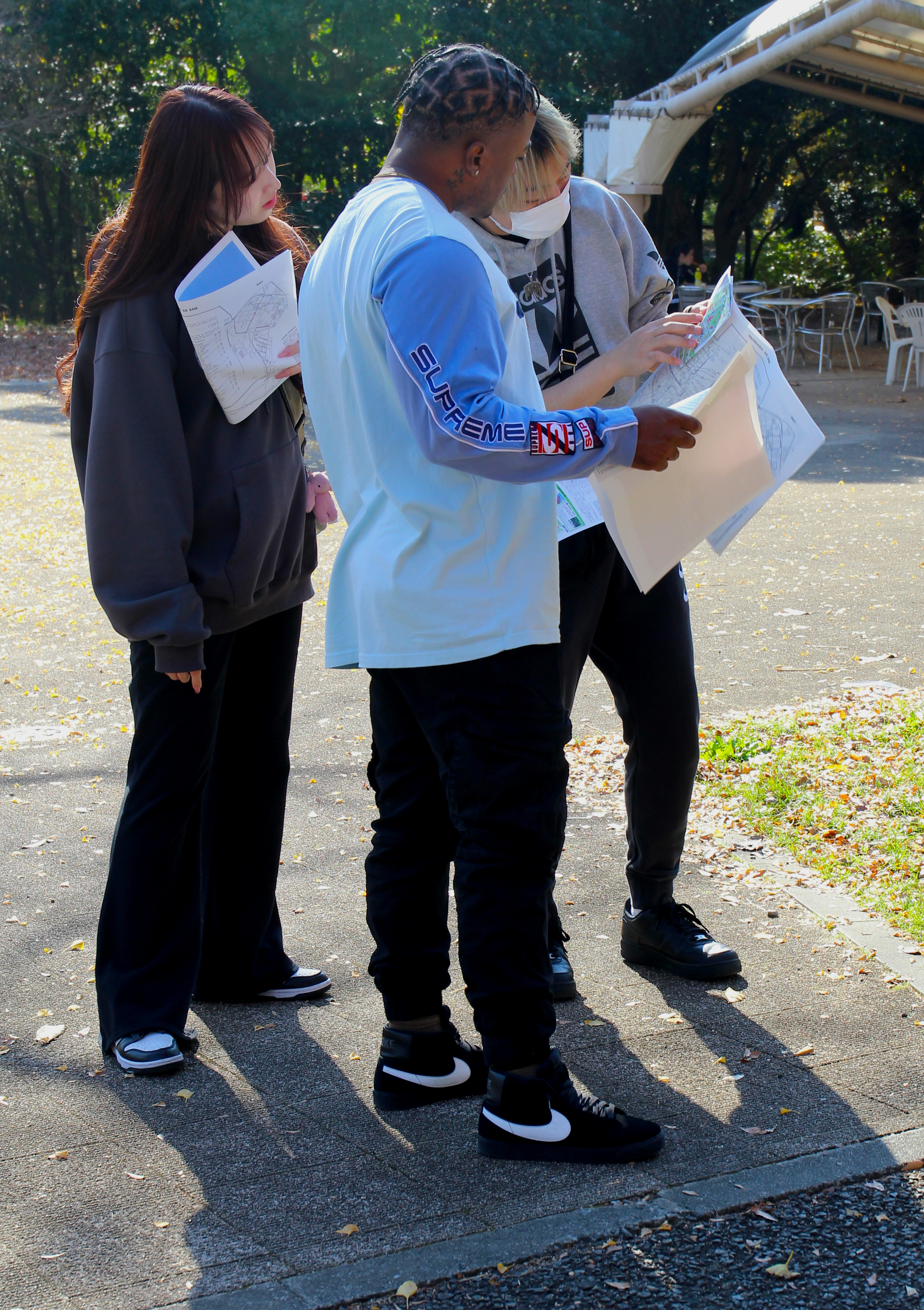

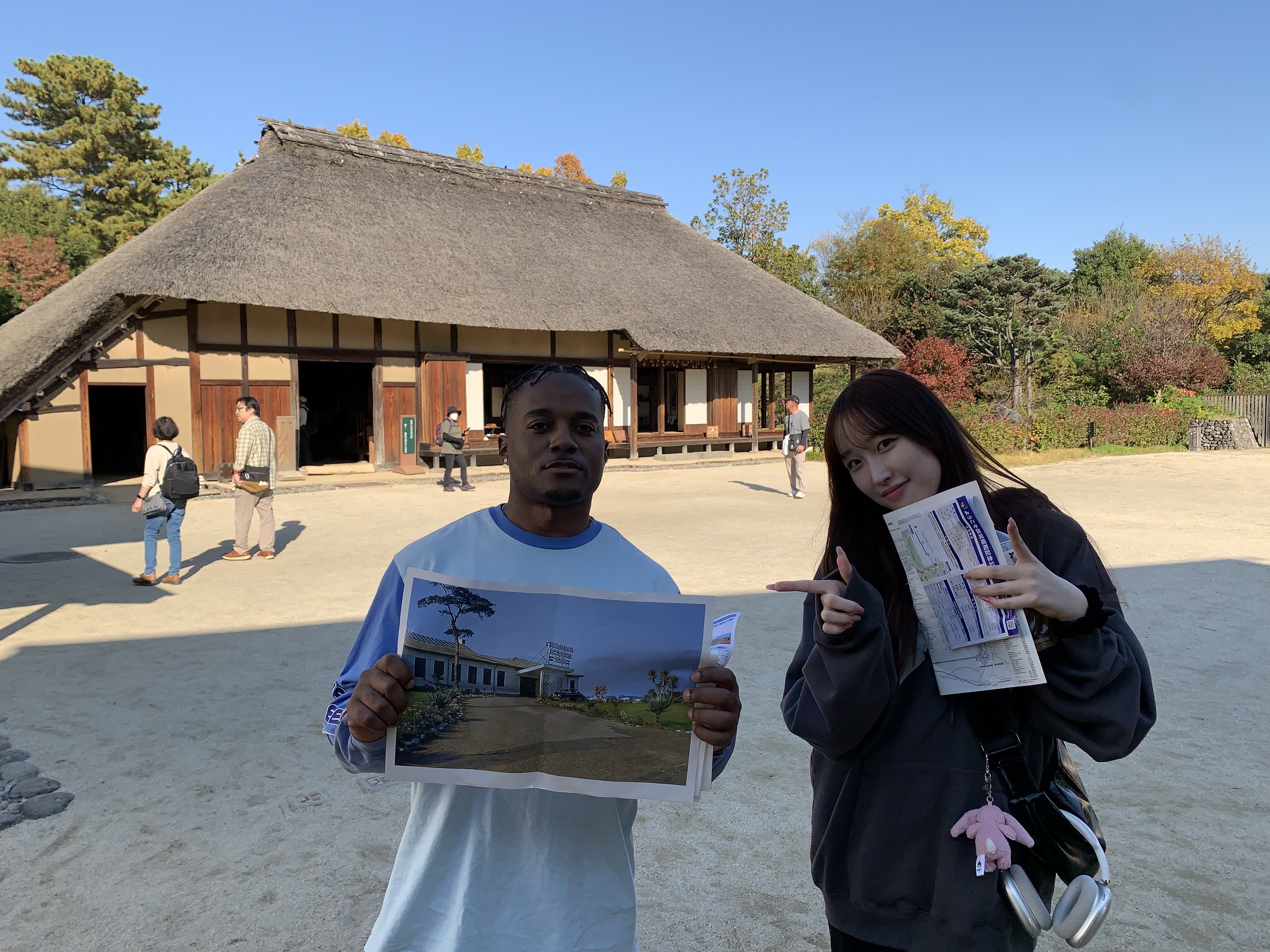

Dr. Tompkins planned the field trip around giving students a chance to match the way the park looked in 1957 to how it is being used today. "Once we were in the park," says Dr. Tompkins, "I broke students into teams. I gave each team an old map of the base (1957), a current map of the park, and a series of (A3-size) photographs from the base taken by service members and their dependents (1950s/1960s). The teams were then sent on a scavenger hunt, with the objective of “un-erasing” history from the park. Once a team identified where an old photograph had been taken, they took a new photo with the old image in hand. After the scavenger hunt, students visited Komorebi Village, a living history museum inside the park that offers a representation of agricultural life in the early Showa period. The day ended sitting around a table with some tasty NY-style pizza and good conversation in Tachikawa."

Photos with caption explanations by Dr. Tompkins can be seen below. Also, for a more expansive account of Showa Kinen Koen and its rich history, please check out this article Dr. Tompkins contributed to NiCHE Canada.